Risk assessment methodology

Overview

The 2023 NRR is based directly on the government's internal National Security Risk Assessment completed in 2022.

How are risks identified and assessed?

Risks were identified for inclusion in the NSRA by consulting a wide range of experts from across UK Government departments, the devolved administrations, the government scientific community and outside of government (for example, in partner agencies, academic institutions and industry). Risks are owned by departments or other government organisations, who are responsible for assessing the impact and likelihood of their risks.

Risks in the NSRA and NRR are assessed as ‘reasonable worst-case scenarios’. These scenarios represent the worst plausible manifestation of that particular risk (once highly unlikely variations have been discounted) to enable relevant bodies to undertake proportionate planning. The scenarios for each risk were produced in consultation with experts and data was collected from a wide range of sources.

The NSRA does not aim to capture every risk that the UK could face. Instead it aims to identify a range of risks that are representative of the risk landscape and can serve as a cause-agnostic basis for planning for the common consequences of risks.

Assessing likelihood

Government departments and agencies responsible for addressing non-malicious risks (for example, severe weather events or accidents) assessed the likelihood of their reasonable worst-case scenario occurring within the assessment period (which is 5 years for non-malicious risks and 2 years for malicious risks) using extensive data, modelling, and expert analysis. The resulting likelihood (expressed as a percentage) is then scored on a scale from 1 to 5, where a score of 1 represents the lowest likelihood and 5 represents the highest likelihood.

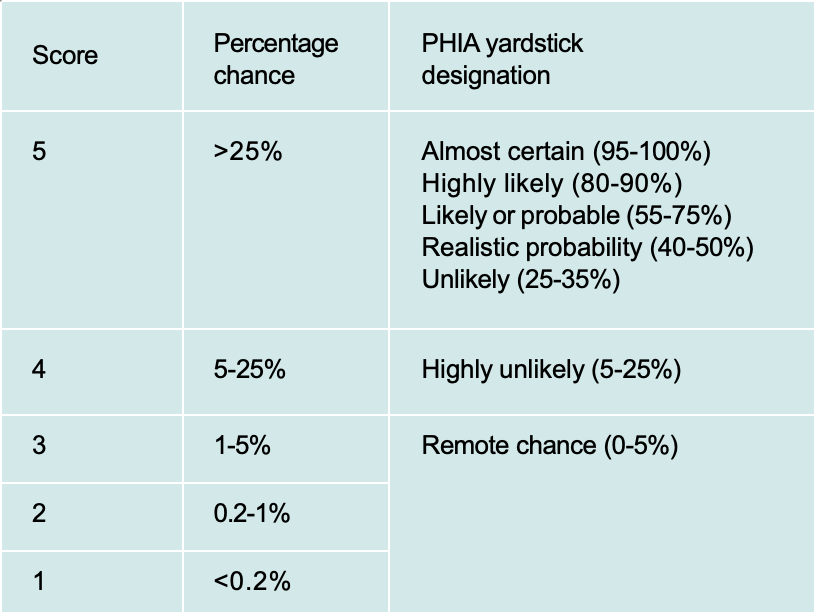

The likelihood of malicious risks (for example, terrorist attacks or cyber attacks) is assessed differently, with scores being calculated via the Professional Head of Intelligence Assessment (PHIA) yardstick (Table 1). The intent of malicious actors to carry out an attack is balanced against an assessment of their capability to conduct an attack and the vulnerability of their potential targets to an attack. These three parameters, informed by data and expert insight, are collated together to form one likelihood score (expressed as a percentage) which is comparable with the likelihood of the non-malicious risks and can be plotted on the same matrix.

Likelihood is presented as the percentage chance of the reasonable worst-case scenario occurring at least once in the assessment timescale and is scored on a 1-5 scale. For both malicious and non-malicious risks, a 1-5 score is evaluated on the following scale:

Table 1

Table 1: Summary detailing the alignment of the final 1-5 likelihood score for NSRA risks, its corresponding percentage chance and the label using the PHIA yardstick.

We use a scale of 1 to 5 for both malicious and non-malicious risks to allow like-for-like comparison between risks, and as a tool to help effective risk visualisation. The highest score (5) represents a greater than 25% likelihood. The reason that this number is relatively low is that all risks in the NSRA are relatively low likelihood events.

Assessing impact

All risks in the NSRA have a wide range of impacts, whether on individuals, businesses, regions or the whole country. To capture this range, the NSRA assesses impact across 7 broad dimensions:

- The impact on human welfare, including fatalities directly attributable to the incident, casualties resulting from the incident (including illness, injury and mental health impacts), and evacuation and shelter requirements.

- Behavioural impacts, including changes in individuals’ behaviour or levels of public outrage.

- The impact on essential services, including disruption to transport, healthcare, education, financial services, food, water, energy, emergency services, telecommunications and government services.

- Economic damage, including numbers of working hours lost

- Environmental impact, including damage to the environment.

- The impact on security, including on law enforcement agencies, armed forces, border security, and the criminal justice system.

- International impacts, including damage to the UK’s international relations and ability to project soft power, disruption to international development, violation of international law and norms, and international displacement and migration.

In addition to the impacts listed above, qualitative data is collected on the disproportionate impacts of the reasonable worst-case scenarios on vulnerable individuals and groups. In accordance with the Public Sector Equality Duty, risk-owning government departments and agencies are required to proactively consider how they can contribute to the advancement of equality and the prevention of discrimination by taking into account the potential effects of their policies, functions, and service delivery on groups with protected characteristics. They are encouraged to go further than the defined list of protected characteristics and to collect data to inform their assessments.

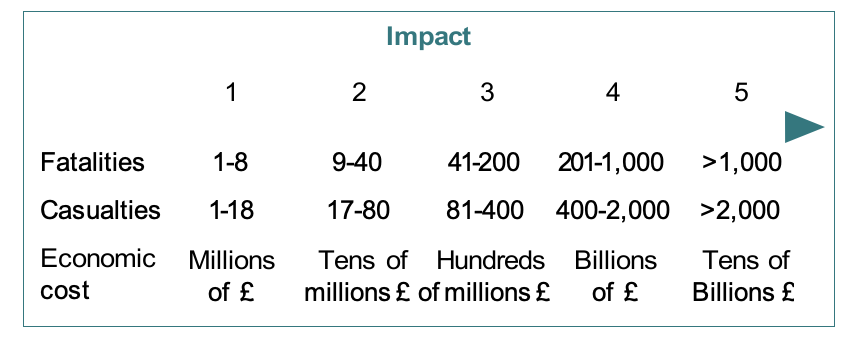

The assessment and scoring of a risk focus primarily on domestic impacts - even where the risk occurs internationally. Each of the dimensions listed above is scored on a scale of 0 to 5 based on the scope, scale and duration of the harm that the reasonable worst-case scenario could foreseeably cause (see table 2 for a selection of example impact scale indicators). These scores are then combined to provide a single overall impact score.

Table 2

Table 2: Example impact scale indicators for fatalities, casualties and economic cost.

Expert challenge

To ensure that the assessment process is robust, risks are reviewed by a network of experts. These include professionals from industry, charities and academia, as well as subject matter experts within government. The role of experts is to provide challenge by:

- Supplementing, clarifying or refining the submitted information;

- Identifying areas of uncertainty;

- Helping to resolve inconsistencies in the scoring of impact;

- Helping to improve communication of impact information; and

- Identifying long-term trends that provide context to the submitted risk.

To facilitate the provision of expert advice, thematic impact review groups were set up to bring together a mix of internal and external expertise. These groups covered individual risk themes (for example cyber and chemical, biological, radiological or nuclear risks), along with the calculated impacts of different risks (for example impacts on essential services or the environment) and a group to look specifically at the disproportionate impacts of the risk scenarios on vulnerable individuals and groups.

Risk matrix

The likelihood and impact of risks are plotted onto a matrix, enabling users to compare risks and inform contingency planning. The NRR matrix below presents the impact and likelihood of a plausible worst-case scenario manifestation of each risk. To enable large differences in impact and likelihood to be shown on the same matrix, non-linear scales have been used. This allows the overall risk landscape to be compared.

The vertical axis shows the impact of each risk. A score of 1 corresponds to the lowest impact, and a score of 5 corresponds to the highest impact. The impact scale is logarithmic and is reflected by the matrix boxes increasing in size.

The horizontal axis shows the likelihood of each risk occuring at least once in the assessment period (2 years for malicious risks, 5 years for non-malicious risks).

The likelihood scale is logarithmic and is reflected by the matrix boxes increasing in size, moving from the bottom left of the matrix to the top right. A score of 1 corresponds to the lowest likelihood, and a score of 5 corresponds to the highest likelihood. The likelihood range in each column, moving from left to right, is five times greater than the previous column. For example, a score 3 risk is approximately five times more likely to occur than a score 2 risk.

Uncertainty is an inherent aspect of risk assessment. Impact and likelihood scores are given a confidence rating that takes account of:

- Quality and reliability of the evidence base;

- Assumptions used in the analysis; and

- External factors that may affect impact and likelihood for example, global events.

Uncertainty in the assessment of the risk is represented on the risk summaries by the lines extending from the plotted dot on each matrix.

Although a majority of individual risks have been plotted onto the matrix, a number of the most sensitive risks have been thematically grouped, bringing together risks that share similar risk exposure and require similar capabilities to prepare, mitigate and respond. This has been done in order to strike the best possible balance between being transparent about risk information whilst protecting sensitive information, for example relating to national security or commercial considerations. The position of each grouped risk on the matrix below is an average of the impact and likelihood scores of all the different risks that belong to that category.

Additional scenarios are provided for a given risk if they would result in substantially different impacts or require significantly different planning. Risks which are marked with a number and a letter represent multiple scenarios of the same risk. For example, the flooding risks are 51a, b and c (coastal, fluvial and surface water flooding respectively).

Chronic risks

Chronic risks are distinct from acute risks in that they pose continuous challenges that erode our economy, community, way of life, and/or national security. Generally, but not always, these manifest over a longer timeframe. While chronic risks also require robust government-led responses, these tend to be developed through strategic, operational or policy changes to address the challenges rather than emergency civil contingency responses. Acute risks on the other hand are risks that may require an emergency response from government, such as wildfires or biological attacks.

Chronic risks can make acute risks more likely and serious – for example, climate change can lead to an increase in the frequency and severity of weather conditions that cause floods and wildfires. Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) has the potential to exacerbate the risk of infectious diseases, for example a pandemic occurring in an environment of ineffective antibiotics could result in higher deaths from secondary bacterial infections. Another risk being examined by the government is artificial intelligence (AI). Advances in AI systems and their capabilities have a number of implications spanning chronic and acute risks; for example, it could cause an increase in harmful misinformation and disinformation, or if handled improperly, reduce economic competitiveness.

The chronic risks included in the 2020 NRR are no longer included due to chronic risks no longer being included in the 2022 National Security Risk Assessment (NSRA).

The NRR is the external version of the NSRA and therefore has aligned with this change. As outlined in the Integrated Review Refresh, the government is establishing a new process for identifying and assessing a wide range of chronic risks. Listed below are a selection of examples of chronic risks previously found in the NRR.

Climate change

The UK average surface temperature has already warmed by 1.2°C since the pre-industrial period, and is predicted to warm further by mid-century, even under an ambitious decarbonisation scenario. The impact of climate change on the intensity and frequency of some climate and weather extreme events is already being observed globally, and these impacts will worsen in the future. Climate change adaptation is a priority for government, exemplified by the UK being one of the first nations in the world to enshrine climate adaptation into law within the Climate Change Act. Climate change can also contribute to longer-term changes to water availability, as well as permanent and irreversible changes such as sea-level rise and alterations to habitats and growing conditions.

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR)

AMR arises when organisms that cause infection evolve in ways to survive treatment. Although resistance occurs naturally, the use of antimicrobials in humans, animal agriculture, plants and crops, alongside unintentional exposure, including through environmental contamination and food, is rapidly accelerating the pace at which it develops and spreads. Each year AMR is estimated to cause almost 1.3 million deaths globally, and 7,600 deaths in the UK. The impacts of leaving AMR unchecked are wide-ranging and extremely costly in financial terms, but also in terms of global health, our ability to undertake modern medicine, food sustainability and security, environmental wellbeing, and socio-economic development. The UK’s 5-year national action plan (NAP) sets out how the government plans to tackle AMR within and beyond our own borders. The NAP focuses on 3 key ways of tackling AMR including: reducing the need for, and unintentional exposure to, antimicrobials; optimising the use of existing antimicrobials; and investing in innovation, supply and access within human, animal and environmental settings.

Serious and organised crime (SOC)

Serious and organised crime, which featured in the 2020 NRR, is now being defined as a chronic risk and therefore removed from this iteration of the NRR. Serious and organised crime is defined as individuals planning, coordinating and committing serious offences whether individually, in groups, and/or as part of transnational networks. Organised criminals threaten the UK’s economic security, costing the UK at least £37 billion every year, with nearly all serious and organised crime underpinned by illicit finance. Serious and organised crime persistently erodes the resilience of the UK’s economy and communities, impacting on citizens, public services, businesses, institutions, national reputation and infrastructure.

The National Assessment Centre, which is the National Crime Agency’s centre for assessed intelligence reporting, publishes an annual National Strategic Assessment that outlines a comprehensive understanding of the serious and organised crime threat to the UK, drawn from all- source intelligence from domestic and international partners.

Artificial intelligence (AI) systems and their capabilities

AI systems and their capabilities present many opportunities, from expediting progress in pharmaceuticals to other applications right across the economy and society, which the Foundation Models Taskforce aims to accelerate. However, alongside the opportunities, there are a range of potential risks and there is uncertainty about its transformative impact.

As the government set out in the Integrated Review Refresh, many of our areas of strategic advantage also bring with them some degree of vulnerability, including AI. That is why the UK Government has committed to hosting the first global summit on AI Safety which will bring together key countries, leading tech companies and researchers to agree safety measures to evaluate and monitor risks from AI.

The National AI Strategy, published in 2021, outlines steps for how the UK will begin its transition to an AI-enabled economy, the role of research and development in AI growth and the governance structures that will be required. The government’s white paper on AI, published in March 2023, commits to establishing a central risk function that will identify and monitor the risks that come from AI. By addressing these risks effectively, we will be better placed to utilise the advantages of AI.

Response capability requirements

The response capability requirements listed in the text are non-exhaustive. They are intended to provide a high–level overview of the potential response capability that may be needed.